Value of Personal Information and Data Breach Class Action Settlements

In certain types of litigations (for example, securities and antitrust class actions), past settlements may be instructive about the potential value or exposure from an ongoing litigation. Our research into settlements in data breach class actions, however, suggests that settlements in these matters may be less informative for assessing the value of a case as whole, as well as the value of the data exposed in the cyberattack.

A unique element of data breach class actions is that there is generally no single “metric” of injury to the proposed class, nor a single unifying economic theory of harm.[1] Similarly, settlements in data breach class actions have certain unique structures and terms.

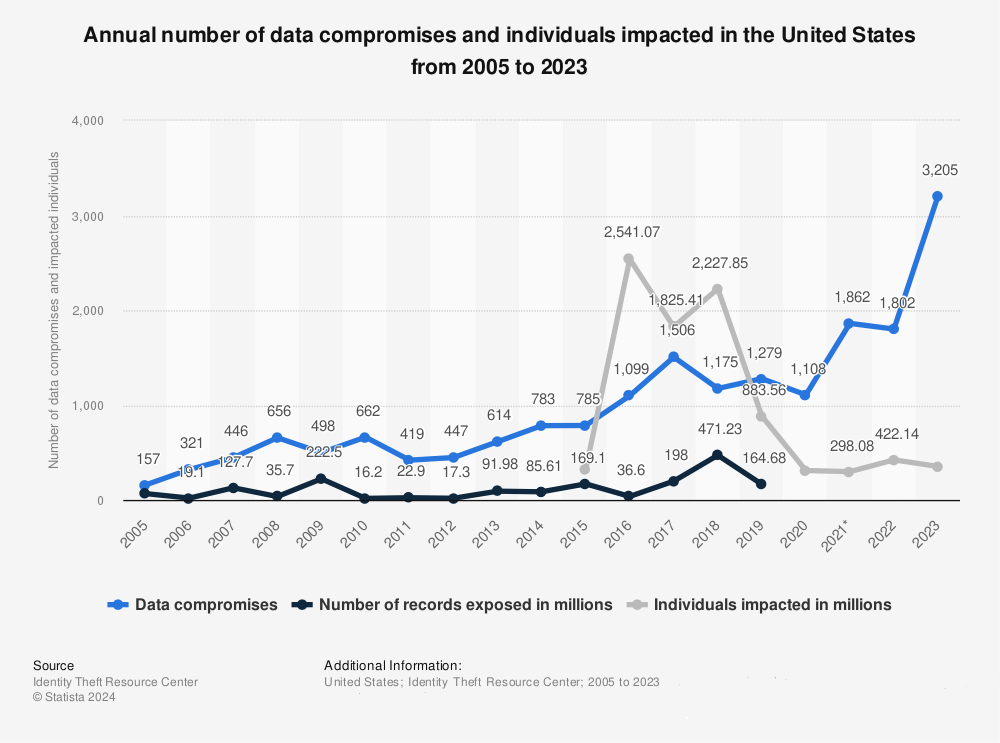

Over the past decade, there has been a substantial increase in the number of data breach events exposing consumers’ and employees’ personally identifiable information (“PII”), such as names, social security numbers, and financial and health information. As Figure 1 shows, the recorded number of these events increased from 447 in 2012 to 1,802 in 2022—an increase of over 300 percent.

Data breach events are frequently followed by classes of individuals whose data were compromised filing lawsuits alleging that the exposure of their data caused them to experience economic harm.[2] Figure 2 shows the number of data breach class actions filed in Federal Courts over time.[3]

Thus far, there have been no data breach class actions that have gone to a verdict. Therefore, practitioners are yet to see how a judge or jury perceive economic harm resulting from a data breach. However, a number of these class actions settled before entering the trial phase, in theory offering information about the value of the breached data.

Having reviewed dozens of settlement agreements in data breach class actions, we found that the structures of these settlements present a unique economic issue. Two examples illustrate the issue:

- In some (typically, higher profile) cases, settlement terms are “top-down”—in that an aggregate settlement amount is determined for distribution to plaintiffs. For example, the settlement in In re: Equifax Inc. Customer Data Security Breach Litigation established (among other provisions) a $380.5 million settlement fund and up to an additional $125 million to satisfy claims for certain out-of-pocket losses, if needed.[4]

- In contrast, many other settlement terms are “bottom-up”—in that no aggregate settlement amount is determined, but rather a consumer gets qualified for a certain amount if they can substantiate their claim. Under these settlements, the actual amount the defendant would pay depends on how many plaintiffs file a claim and the individual value of each claim. For example, the settlement in Chacon et al v. Nebraska Medicine provided for up to $300 per Settlement Class Member, up to $3,000 per Settlement Class Member for extraordinary loss, and up to 6 hours at $20 per hour for time spent dealing with the data incident.[5] There was no aggregate cap on the settlement fund.

Finally, many settlements include non-pecuniary terms that further distance the settlement from the harm to class members. For example, the Equifax settlement includes a financial commitment to Equifax spending $1 billion on data security and related technology. While the money spent on improving the IT security may benefit customers in the future by lowering the probability of future breaches, it does not correspond to injury to plaintiffs and economic value of data.

CITATIONS

[1] For example, proposed class members might claim harm due to the time spent mitigating potential effects of the breach and the associated loss of productivity, out-of-pocket costs for identity theft protection services, diminution in value of personal information, fraudulent misuse of stolen information, continued risk of future misuse, and loss of the benefit of the bargain with Defendants to provide adequate data security.

[2] While certain high-profile data breaches—and associated litigations—are covered in the press, overall patterns in these cases are generally not well understood. As Romanosky et al. observed: “very little is known about the drivers, mechanics, and outcomes of those lawsuits, making it difficult to assess the effectiveness of litigation at balancing organizations’ usage of personal data with individual privacy rights.” Romanosky, S., Hoffman, D. and Acquisti, A. (2014), Empirical Analysis of Data Breach Litigation. Journal of Empirical Legal Studies, 11: 74-104. https://doi.org/10.1111/jels.12035

[3] Note that some data breach events may cause tens of individual lawsuits to be filed. These tend to eventually be consolidated into a single multidistrict litigation. However, the number of filings in the most recent year likely overstates the number of filings that can be resolved through a settlement, as individual cases have not yet been consolidated.

[4] Order Granting Final Approval of Settlement, Certifying Settlement Class, and Awarding Attorney’s Fees, Expenses and Service Awards, In re: Equifax Inc. Customer Data Security Breach Litigation, MDL Docket No. 2800 No. 1:17-md-2800-TWT, United States District Court Northern District of Georgia, Atlanta Division, January 13, 2020.

[5] Plaintiffs’ Motion for Attorneys’ Fees, Costs, and Service Awards and Memorandum in Support, Chacon v Nebraska Medicine, United States District Court for The District of Nebraska, CASE NO. 8:21-cv-00070-RFR-CRZ, August 19, 2021. The settlement was approved on September 15, 2021.

Experts

- Partner

- Partner